Popular Philippine music has taken many forms over the years, from the rise of traditional folk love songs like the kundiman, to covers, rock, the P-pop wave, and everything in between. However, the roots of contemporary Filipino music as we know it today can be traced back to what many call the “golden age,” which is used to denote the time period where original compositions written in Filipino languages emerged and dominated the mainstream for the first time.

In the mid-1970s, the influence of the American occupation in the country was still felt in the Filipino mainstream. Tina Arceo-Dumlao, author of Himig At Titik: A Tribute to OPM Songwriters, shared in a “History of OPM” talk with the Organisasyon ng mga Pilipinong Mang-aawit that with the overwhelming dominance of American music, it was considered unthinkable to produce original songs, especially writing lyrics in the Filipino language itself.

Yet, disco-pop band Hotdog broke through this barrier and proved that original Filipino compositions could be commercially successful, ushering in a new era of pop music that was created by and for Filipino audiences. The late Dennis Garcia, Hotdog’s lyricist, coined the term of what this era would be eventually named: Manila Sound.

Joining Hotdog at the forefront of this movement were acts like Cinderella, The Boyfriends, and VST & Company. It was the era of disco and funk with a Filipino twist — hits like “Awitin Mo, Isasayaw Ko” and “Macho-Gwapito” ruled the disco mania that swept the Philippines. On the other end of the Manila Sound spectrum were the slowed down and dreamy pop tracks such as Sharon Cuneta’s “Mr. DJ,” Cinderella’s “Bato Sa Buhangin,” and Rico J. Puno’s “The Way We Were.”

While the musical elements of Manila Sound were still heavily borrowed from the country’s Western influences, what made it uniquely Filipino were the images, themes, and concepts that shined in its lyrics. One of the hallmarks of the genre was the use of Taglish (a mix of Tagalog and English) and street slang to create a songs that captured Filipino wit and the language of the time. Cinderella’s “T.L. Ako Sa’yo” peppered in Filipino slang like “dehins” while Hotdog’s “Manila” used Taglish to paint a picture of the city in the ‘70s. The era of Manila Sound signaled a catalyst in Filipino pop music — one that argued that Filipino music didn’t have to be just a mode of entertainment, but rather a reflection and celebration of Filipino culture.

Towards the end of the ‘70s finally came the birth of the terminology for Filipino pop music as we understand it today: Original Pilipino Music (OPM).

Finding our groove

The term “OPM” was coined by the late Danny Javier of the APO Hiking Society. Javier led the radio promotions at his day job in Jem Records, an independent record label that not only managed APO Hiking Society, but also the likes of Eddie Munji, Ryan Cayabyab, and Maria Cafra. In an interview with the Daily Tribune, former Jem Records staff and photographer Eddie Boy Escudero shared that “OPM” was originally used as a “marketing strategy” to differentiate their company from the rest of their competition. Unlike other companies at the time, Jem Records did not distribute music from large foreign labels. Instead, they produced and distributed original Filipino compositions, hence the name OPM. In 1978, the term was first used in the title of Hajji Alejandro’s album, Strictly OPM.

Arceo-Dumlao denotes this era as “an explosion of creativity,” where Filipino musicians were energized to compose songs in their local languages for the local audience. For rock, you had the likes of the Juan Dela Cruz Band, Sampaguita, Maria Cafra; folk had Freddie Aguilar, Asin, Florante; novelty music had Yoyoy Villame; and mainstream pop had Gary V, Jose Mari Chan, Rey Valera, and more. All of these contributed to what Jim Paredes of APO Hiking Society once described as, “the soundtrack of Filipino life.”

Beyond terminology, the ‘70s and ‘80s saw an active effort to invest in Filipino pop music, which included the establishment of the first songwriting competition in the country, the Metro Manila Popular Music Festival or Metropop in 1977. It launched and nurtured the careers of some of the biggest songwriters and composers in modern Filipino history, such as Freddie Aguilar, Ryan Cayabyab, and the like.

Metropop entered at a pivotal moment in Filipino music history, where everyone came together to jumpstart a culture that encouraged Filipinos to not just listen to original compositions, but to create music that represented their own experiences. It served as a reaction against centuries of Western influence on Filipino culture. From the ‘70s onwards, the country was determined to carve out our own identity through music.

On our own terms

Despite the OPM movement ushering in the popularity of Filipino music in the mainstream, this was largely, if not completely, dominated by Tagalog music. It was rare for music from Visayas and Mindanao to gain the same popularity as their northern counterparts.

A few years after the creation of Metropop, the Cebu Popular Music Festival or Cebu Pop was established in 1981. In the same way that Metropop encouraged Filipinos to write and perform songs in Filipino, Cebu Pop cultivated Bisaya songwriters and awarded them in the same way. In 2012, a parallel songwriting competition named the Visayan Pop Music Festival, or Vispop for short, was born.

“We [already] had a community of songwriters who were unabashedly Bisaya,” shares Vispop founder Jude Gitamondoc in an exclusive interview with Billboard Philippines. “There came a time when Cebu Pop was the tastemaker…a seedbed of young and good songwriters such as Jimmy Borja who were writing in Bisaya. Cebu Pop also became a seedbed for singers as well, such as Vina Morales, Anna Fegi, and Raki Vega.”

Gitamondoc goes on to talk about the parallel music scenes that were flourishing in the Visayas at the same time, such as reggae bands like Junior Kilat; rock bands like Aggressive Audio and Missing Filemon; the acts that wrote in English like Cattski, Urbandub, and Franco; all co-existing with Cebu Pop.

“Vispop was a mix of these influences,” he says. “The vision was to marry existing traditions of Bisaya songwriting with more contemporary trends of pop music.”

Vispop became the first songwriting competition of its kind to integrate songwriting workshops as part of their festival campaigns. Since then, other songwriting competitions followed suit.

“That was one of the first ideas when I pitched Vispop in 2010,” he says. “We do not wait for the entries to be submitted to us — we reach out to young songwriters and teach them how to write in Bisaya.”

For Gitamondoc, training Bisaya songwriters was a priority. Now, he’s observed that songwriters are unafraid to write in Bisaya, despite the challenges of writing in a different language. Today, crowds gather to hear performers sing in the language they share. Truly, the mission of Vispop’s predecessors still rings true today.

While acts from Bisaya-speaking regions have broken into the mainstream, very few Bisaya language songs have reached the same popularity as songs written in Filipino. This may have contributed to the differentiation of OPM with labels of “local” and “regional” music, to name a few.

Gitamondoc retorts by saying, “OPM is not just Manila. That’s part of our advocacy in Vispop: to show the many different Filipino stories told in many different Filipino voices. It’s time for us to hear from the rest of the Philippines.”

The beat of our own drum

To understand what Filipino pop music is, it’s not only important to look back at where Filipino music has been, but where it’s headed today, especially as the pop music landscape moves towards accessibility. The advent of digital streaming platforms and music production software has made it easier for artists to release their own music without the traditional support of a label or the pressure of record sales.

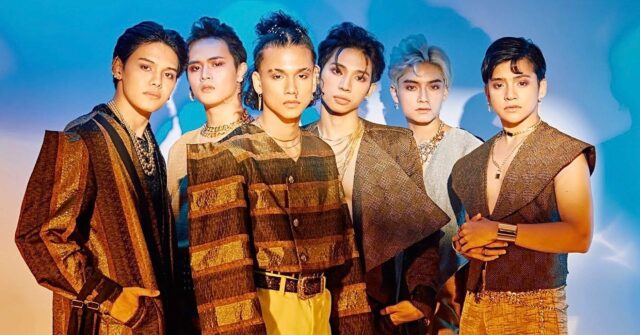

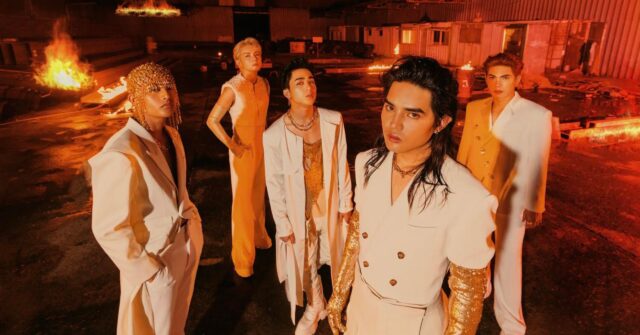

With music production being more accessible than ever before, artists are now creating music on their own terms. Today, acts like Dilaw, Lola Amour, or SB19 are continually reaping the fruits of musicians who paved the way for Filipino music.

As the boundaries of popular music expand, there needs to be an expansion of our common understanding of OPM, especially in a country with diverse ethnocultural and linguistic identities. With the dominance of Tagalog music under the umbrella of OPM, many musicians of different Filipino identities find it difficult to associate themselves with the term.

The country’s pop music scene has been a constant challenge of definitions and redefinitions — first, an emulation of the Western influences that ran rampant in our country; second, a reclamation of our own language and culture through music; and next, a challenge to expand our horizons to create a truly inclusive Filipino musical landscape. Navigating the next step that Filipino pop music will take is never clear cut. However, in today’s ever-changing world, that decision is no longer in the hands of few but rather, in everyone’s hands.

A version of this story appeared in Billboard Philippines’ pop issue, dated Oct. 15, 2023.