In today’s world, it seems that we might know everything there is to know about Filipino music — Manila Sound started in the ’70s with the rise of groups like Hotdog and VST & Company; ‘OPM’ was coined in the ’80s; Pinoy rock surged into the mainstream in the ’90s; and the reign of P-Pop took over in the late 2010s until now.

Many of these facts have been passed down through oral traditions, documentaries, recorded interviews, and so on and so forth. However, the Philippines has a long and rich history of music journalism that captured and covered these momentous events as they unfolded in front of their very eyes. Perhaps it’s an opinion column by the late Senator Miriam Defensor Santiago talking about her thoughts on the up-and-coming genre, Manila Sound. Or maybe it’s a review of Filipino pop music history, published in the program brochure of the 3rd Metro Manila Popular Song Festival in 1980. Maybe, even, an interview with Gary Valenciano, Celeste Legaspi, and National Artist for Music Ryan Cayabyab on their predictions of who will be the pop superstar of the ’90s.

These scans are just a glimpse into the lost history of Filipino music throughout the ages. Many of the newspapers, tabloids, and magazines featured have long since been discontinued. The UP Diliman College of Music is currently archiving these materials at their library in the Jose Maceda Hall. However, small talk with the librarians and library aides reveal that these articles are in danger of being lost to time due to the lack of manpower and resources to digitize these materials. Many of the pages in the newspapers and tabloids are currently disintegrating due to time.

As more strides are made in Filipino music, it also brings to mind the need to preserve the narratives that brought us to where we are now, before we lose these stories to time.

’40s and ’50s: The age of classical music

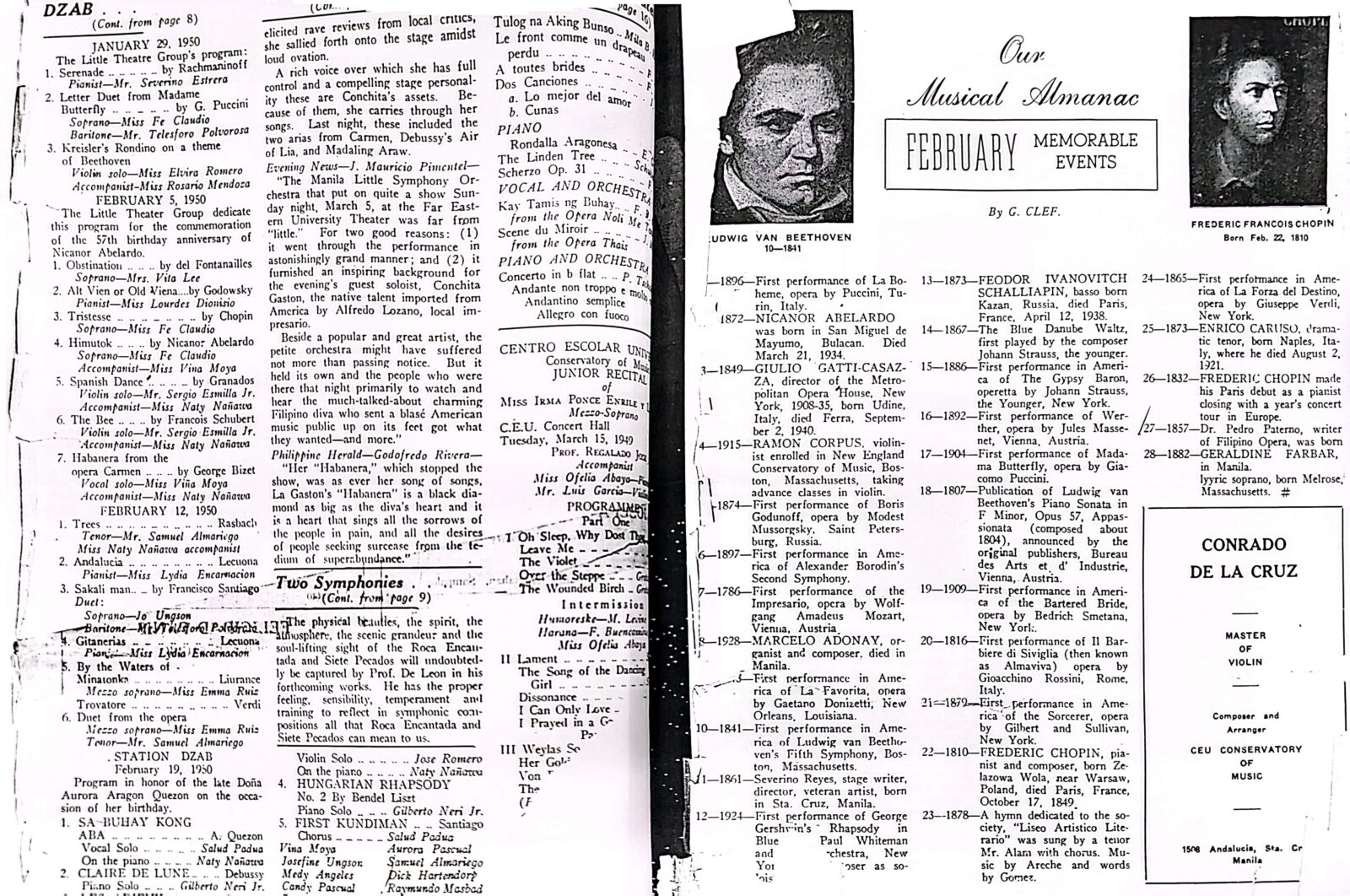

January-February 1950 issue of Musical Philippines.

Musical Philippines was a local music magazine that was in circulation sometime in the ’40s and ’50s. Little information about the publication is available online, and searches for ‘musical philippines magazine’ bring up zero references for this magazine. In the 1950 edition available at the UP College of Music Library, its pages feature catalogues of various classical music recitals, program notes on recent performances, and even features of a “Manila Music Lovers Society,” which seemed to give awards to esteemed classical instrumentalists at the time.

Musical Philippines, January to February 1950 Issue.

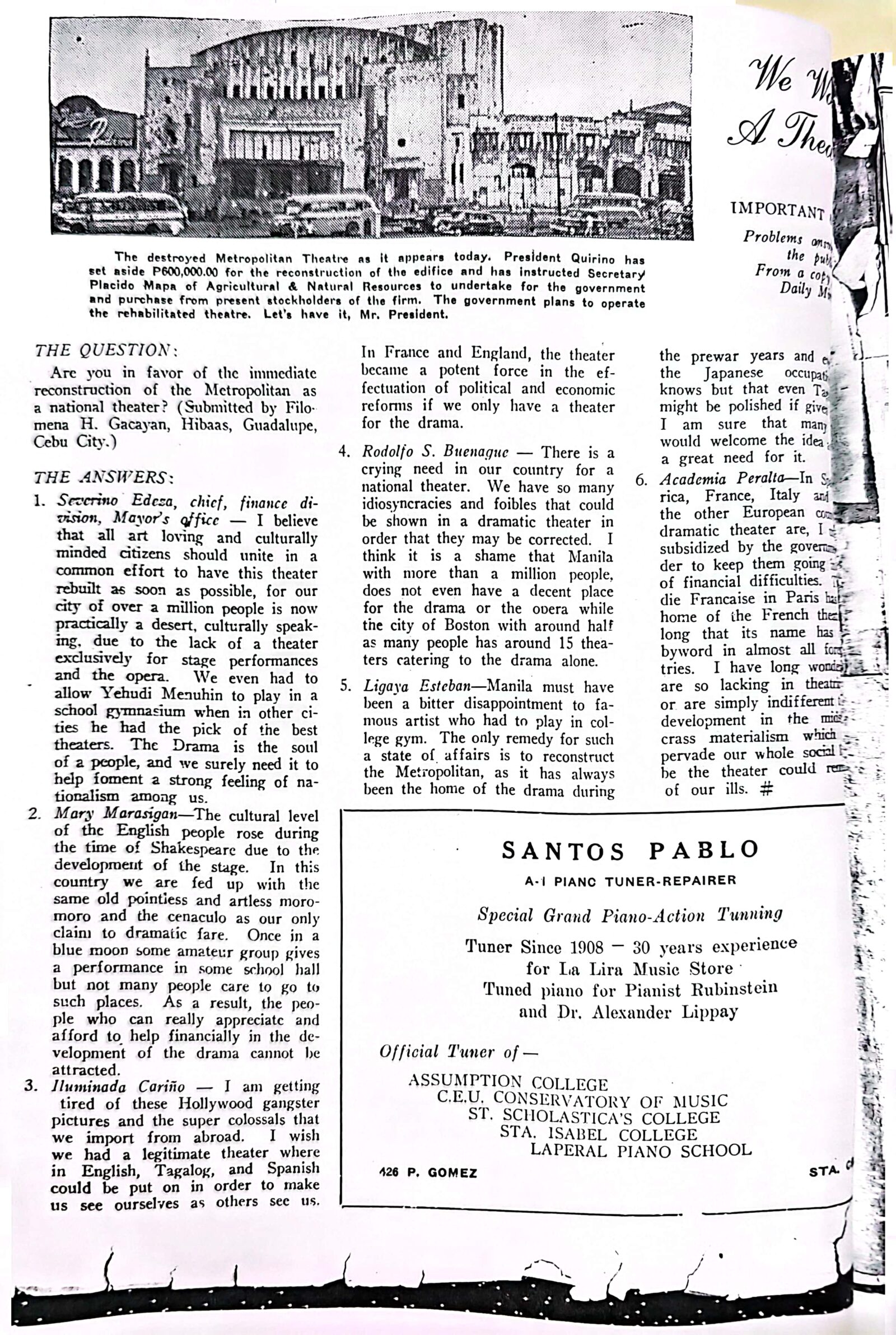

This edition also had a “survey,” where different people weighed in on if the Metropolitan Theater should be immediately reconstructed and made into a national theater. Who would’ve thought that a little over seven decades later, the Metropolitan Theater would be reopened on its 90th anniversary in December 2021 and has been named a National Cultural Treasure.

Musical Philippines, January-February 1950 Issue.

Late ’60s and ’70s: Documenting the creation of ‘Manila sound’ and ‘OPM’

The Philippines in the ’60s and ’70s is marked by Ferdinand Marcos Sr.’s Martial Law. The politics of the country directly affected the music scene as well — as seen in this program brochure from the 1977 Sandiwa National Music Festival at the Folk Arts Theater. The former PR manager of Vicor Music (now acquired by Viva) Norma Japitana penned a piece about the acceptance of Filipino pop music, where she talked about how Pinoy rock legends Juan dela Cruz Band captured the hearts of the nation for Filipino-made songs. Japitana also writes about how Rico J. Puno — then an up-and-coming artist — was predicted to “go even bigger this year.”

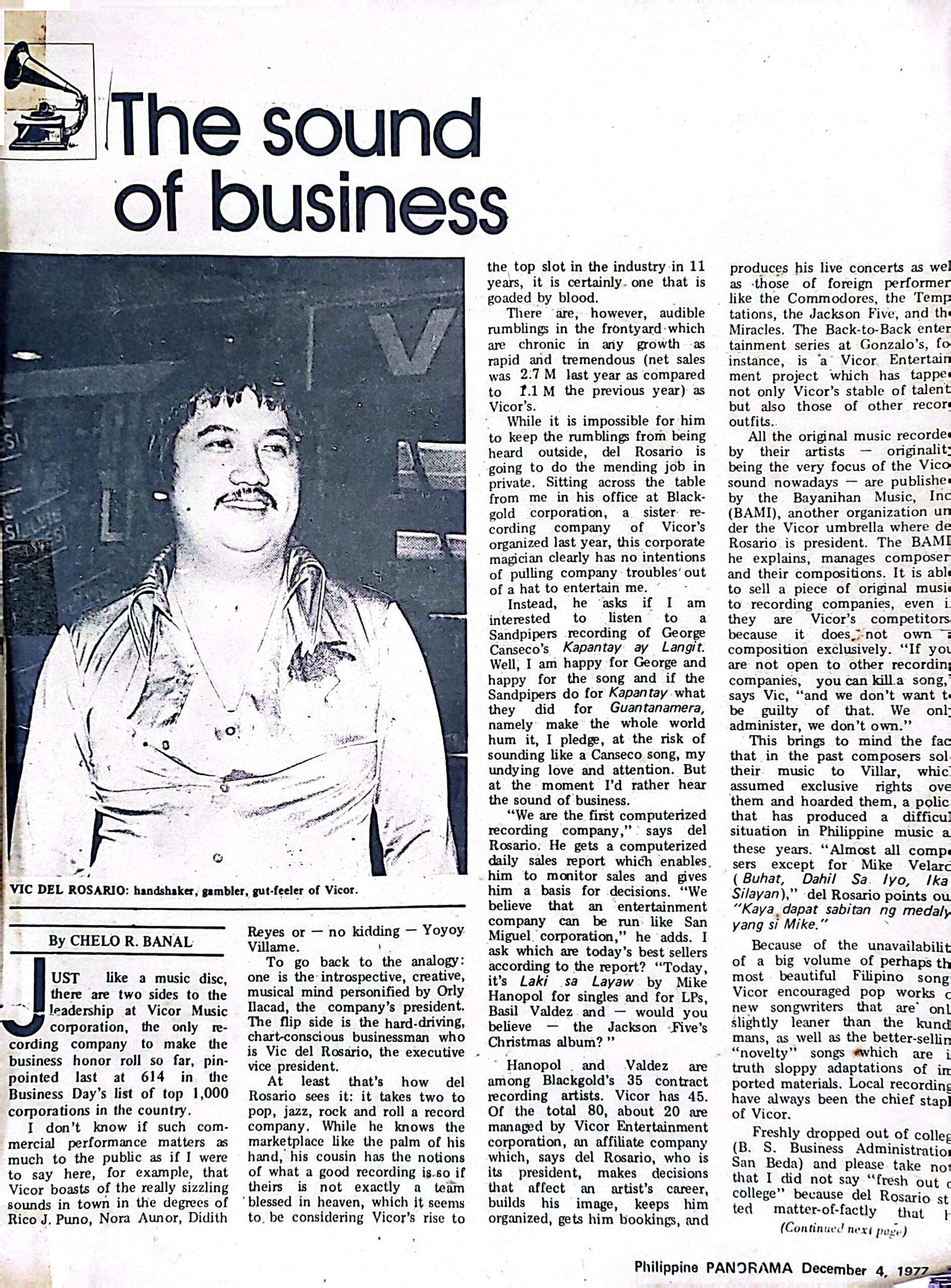

The magazine Philippine Panorama also commented the rise of Filipino-made music, such as in the 1977 feature piece “Tagalomania,” where writer Eric S. Giron wrote that “in singing today, Tagalog is It, baby.” Features on the biggest names in Filipino music as well were very prominent, such as Hajji Alejandro, record label executive Vic del Rosario, Mike Hanopol, and discussions on what a “distinct and unique Filipino sound” should be.

Eric S. Giron in December 4, 1977 issue of Philippine Panorama.

The late Senator Miriam Defensor Santiago, after her time in Michigan, wrote a piece in the December 1977 edition of the Philippine Panorama. When describing the genre’s rising popularity, she wrote, “The Manila Sound which blooms today in the hybrid gardens of Ermita and Makati, gives free rein to the use of the Filipino voice and the exploitation of our instrumental resources.” Atang de la Rama, the first Filipina film actress, was also recognized for her role as the “Queen of Kundiman and of the Zarzuela.” In a feature titled, “So Quickly Forgotten, But Endlessly Applauded Whenever Remembered,” they recounted her career when she turned 74 years old in 1979.

’80s and ’90s: Championing Pinoy music here and to the world

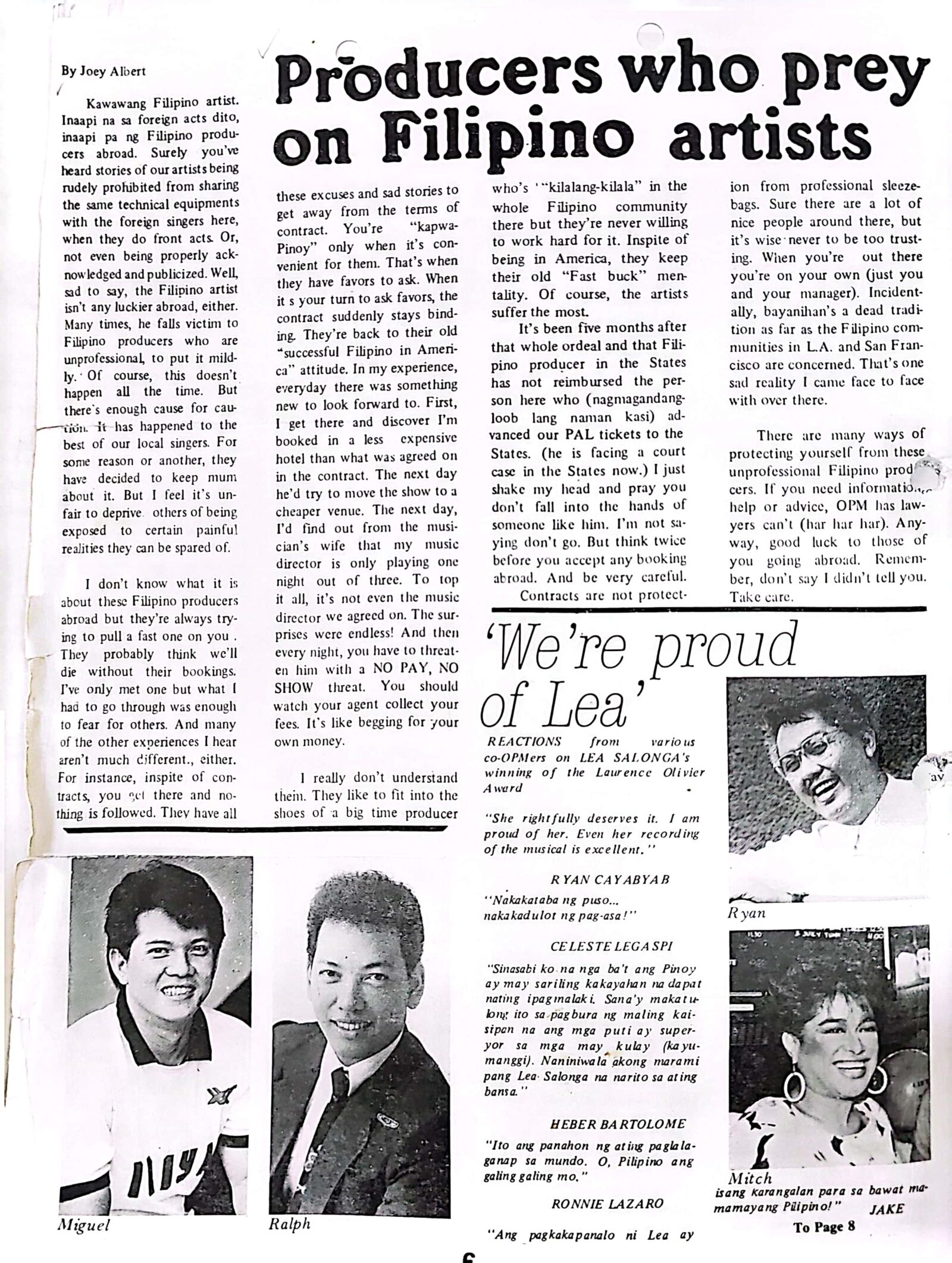

In the ’80s and ’90s, the love for OPM was in full swing. The Organisasyon ng Pilipinong Mang-aawit (OPM) was formed, and they had their own newsletter titled OPM News, where they shared events of OPM members, transparency reports, as well as thinkpieces on Filipino music.

Written by Joey Albert in Organisasyon ng mga Pilipinong Mang-aawit, date unknown.

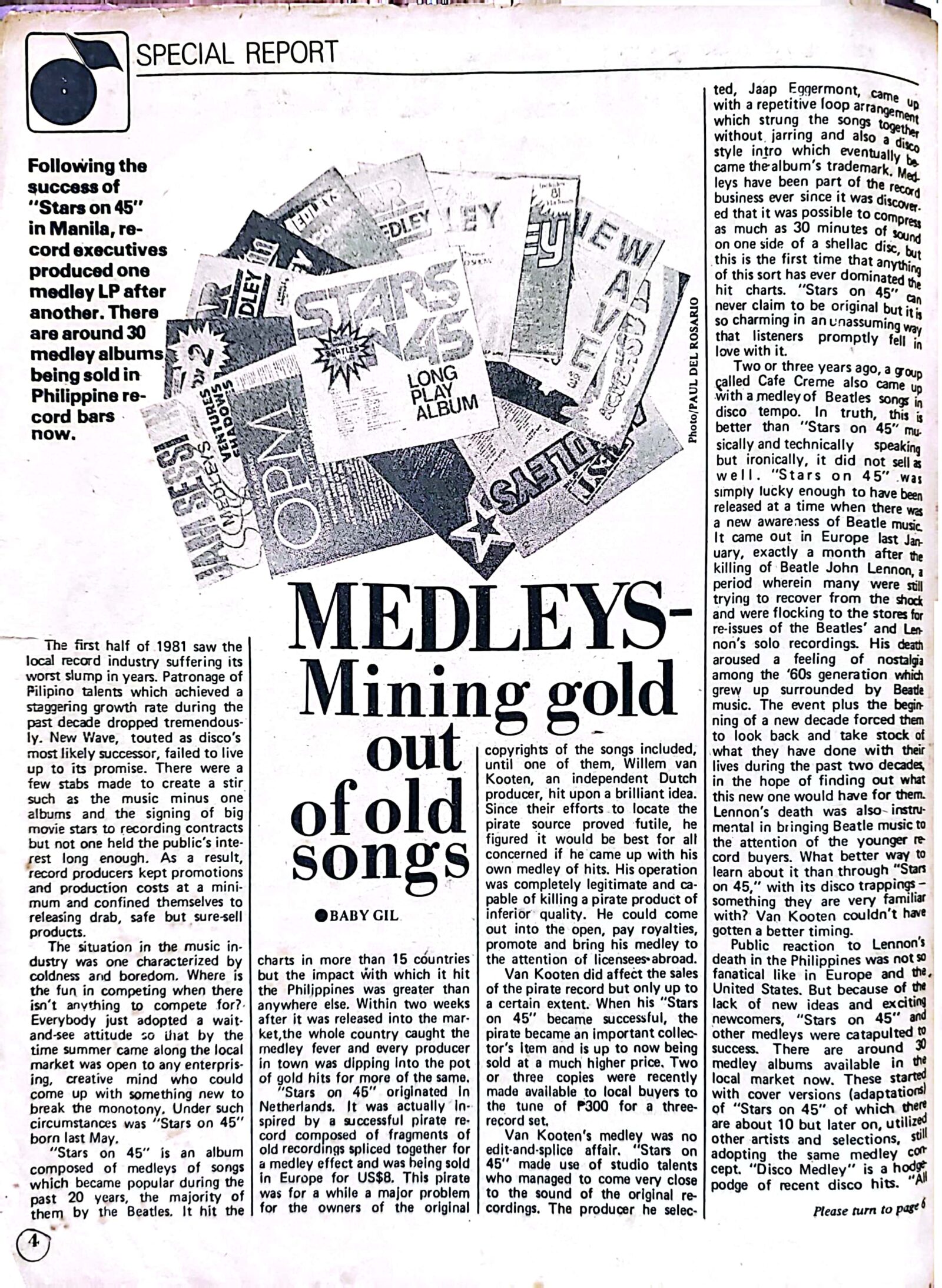

The ’80s also saw broad coverage and commentary on Parade magazine, where their 1981 issue tackled things like a review of the fourth Metro Manila Pop Festival and thinkpieces on the prevalence of medleys at the time.

Written by Baby A. Gil in 1981 issue of Parade.

In the ’90s, they documented their lobbying efforts to protect artist and performers rights in the country. The ’90s also saw a plethora of features on then-rising artists who would end up becoming OPM giants, such as this 1993 double feature on the Eraserheads and Wuds in the now-defunct Malaya.

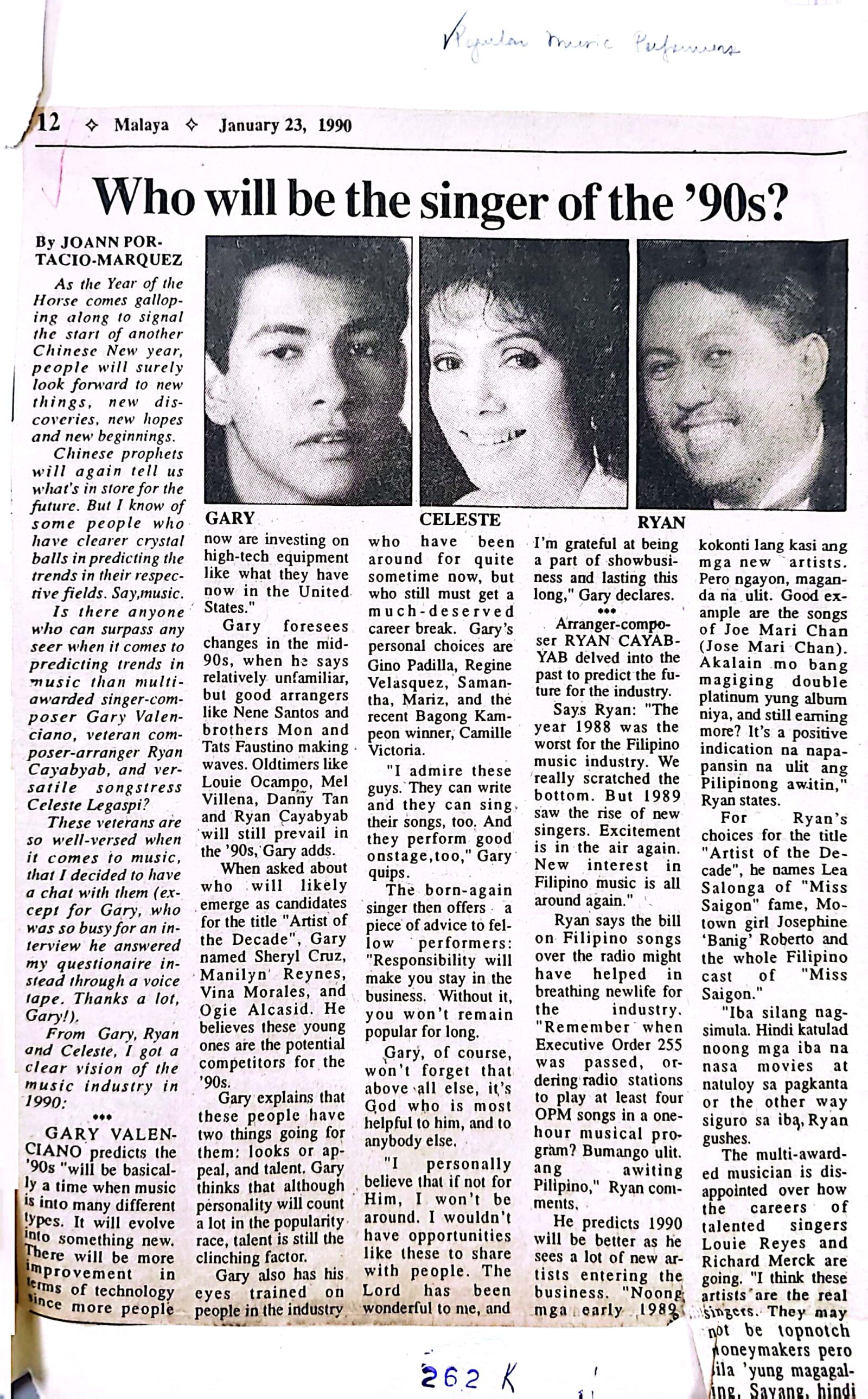

Music writers also sat down with celebrated artists like Gary Valenciano, Celeste Legaspi, and Ryan Cayabyab to talk about how the future of Filipino music could look like in the ’90s. Valenciano’s own predictions of how music in the ’90s ranged from things like how music would evolve into different types, the improvement in technology would unlock more opportunities for Filipino music to grow, and more.

Written by Joann Portacio-Marquez for Malaya, dated January 1990.

A Philippine music and entertainment variety newspaper was also in circulation in the ’90s titled Balitaktakan which featured commentary on OPM and Philippine arts. A piece by Nestor Cuarto titled “Radyo OPM, The Ultimate Dream” detailed the call for more radio stations to feature OPM songs in their programs.

The Philippine Panorama also celebrated its 25th anniversary in 1993, and their anniversary issue included a piece by National Artist for Music Dr. Lucrecia Roces Kasilag on finding the definition of Philippine cultural nationalism through music. “Music has become a strong factor in arousing nationalism and love of country,” she writes.

Written by Dr. Lucrecia Roces Kasilag in August 1993 25th anniversary issue of Philippine Panorama.

2000s and 2010s: Profiling today’s artists

In the 2000s and 2010s, Filipino music found its way into the columns of various mass media publications. Columns such as Igan D’Bayan’s “Audiosyncrasy,” Jim Paredes’ “Humming In My Universe,” and Baby A. Gil’s “Sounds Familiar” gave a space for reviews, thinkpieces, and commentary on the state of Filipino music.

There were also features that captured what Filipino music was like at the time, such as this Manila Bulletin interview with Rivermaya post-Bamboo’s departure, with the band saying that they “didn’t blame Bamboo for decisions that [the] record company made.”

Written by Jojo P. Panaligan for the Manila Bulletin, dated Sept. 23, 2004.

Igan D’Bayan’s review of the Lourd de Veyra-fronted band Radioactive Sago Project’s T****namo Andaming Nagugutom Sa Mundo Fashionista Ka Pa Rin (F*** You There Are So Many Hungry People In The World And You’re Still A Fashionista) shared thoughts like “[The album] is Sago’s most mature opus to date.”

Written by Igan D’Bayan for YoungSTAR, date unknown.

Overall, the advent of the internet has made it easier to archive and document the Filipino music scene — whether it’s through writing, photos, videos, or audio recordings. However, the challenge remains to better preserve the long history of Filipino artistry, especially with documents and recordings that aren’t available online.

Music has always been a reflection of the Filipino experience. As we move forward as a nation, the past is what lays down the foundation for the future. Questions surrounding Filipino music have been posed by writers and artists decades ago have even remained relevant in this day and age. Our challenge now as a country is: by preserving our past, where can we go next?

Billboard Philippines would like to give special thanks to the UP College of Music Library for allowing us to access and publish these materials.