If there’s anything that Filipino hip-hop has proven over the last year, it’s that the genre is not to be taken lightly. In just a few months, hip-hop has dominated the Billboard Philippines Songs Charts, with O Side Mafia becoming the first Filipino hip-hop group to reach number one, and Hev Abi occupying the chart’s top spots.

It’s a recognition that is, to say the least, long overdue. Hip-hop has been present in the country since the ‘80s and has only grown exponentially since. It’s not just the music that’s taken hold in the country; hip-hop culture — graffiti, streetwear, breakdance, DJ-ing, and the like — has found its way into every crevice of Filipino life.

In each bar and flow, these artists carry the stories of our struggles and successes that only hip-hop can tell. It comes off as aggressive and maybe a tad brash at times, but that unapologetic streak has defined the genre in a way that no other genre can do. With that as the heart of the community, it’s no surprise that the genre has been both big with listeners and its budding artists throughout the years. Today, you have new producers and scrappy MCs using their own languages to hash out their experiences set to buzzing bass notes, the trill of a hi-hat, or a synth line. They all play around with technology to produce different sounds, influences, and elements in an effort to create something new.

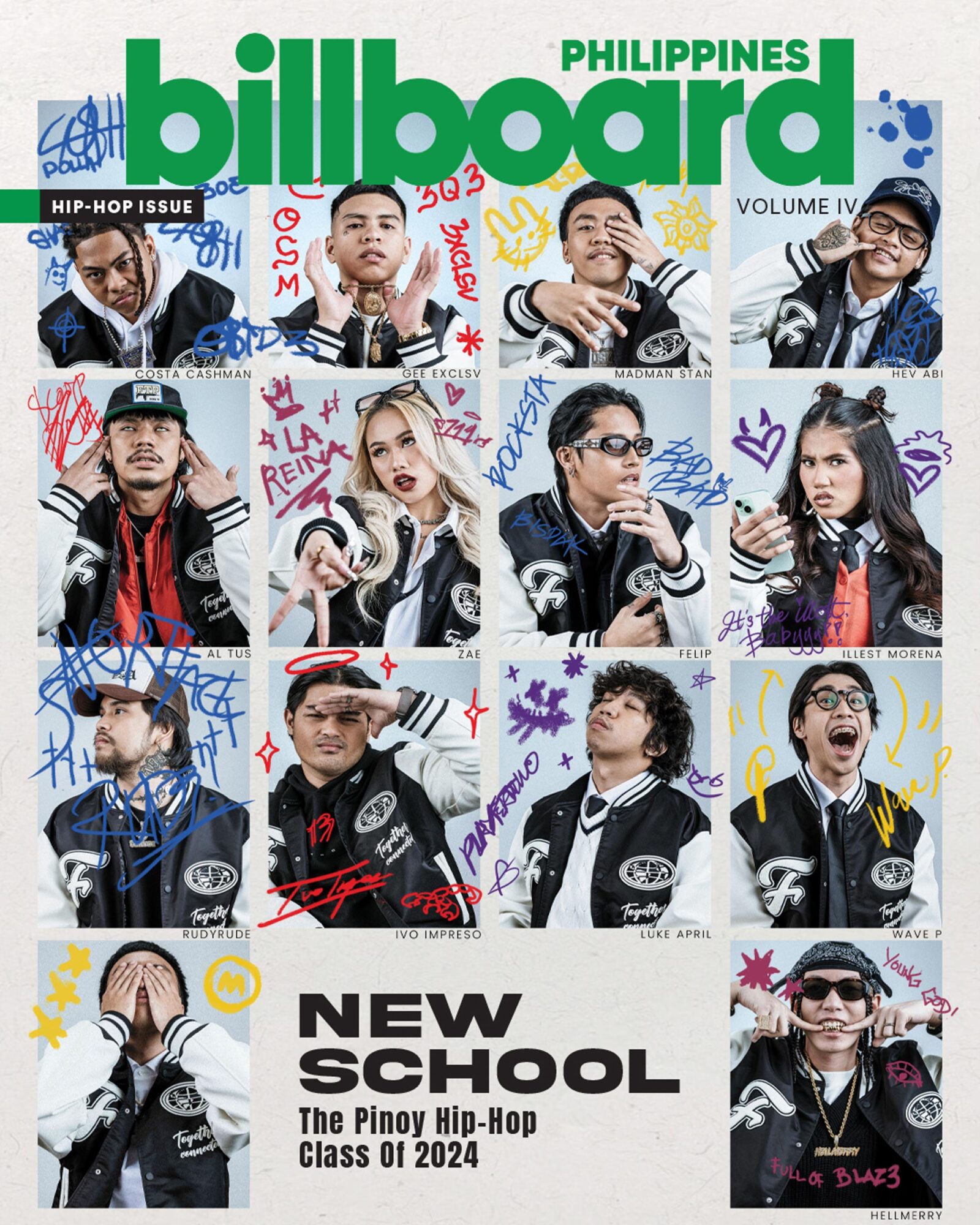

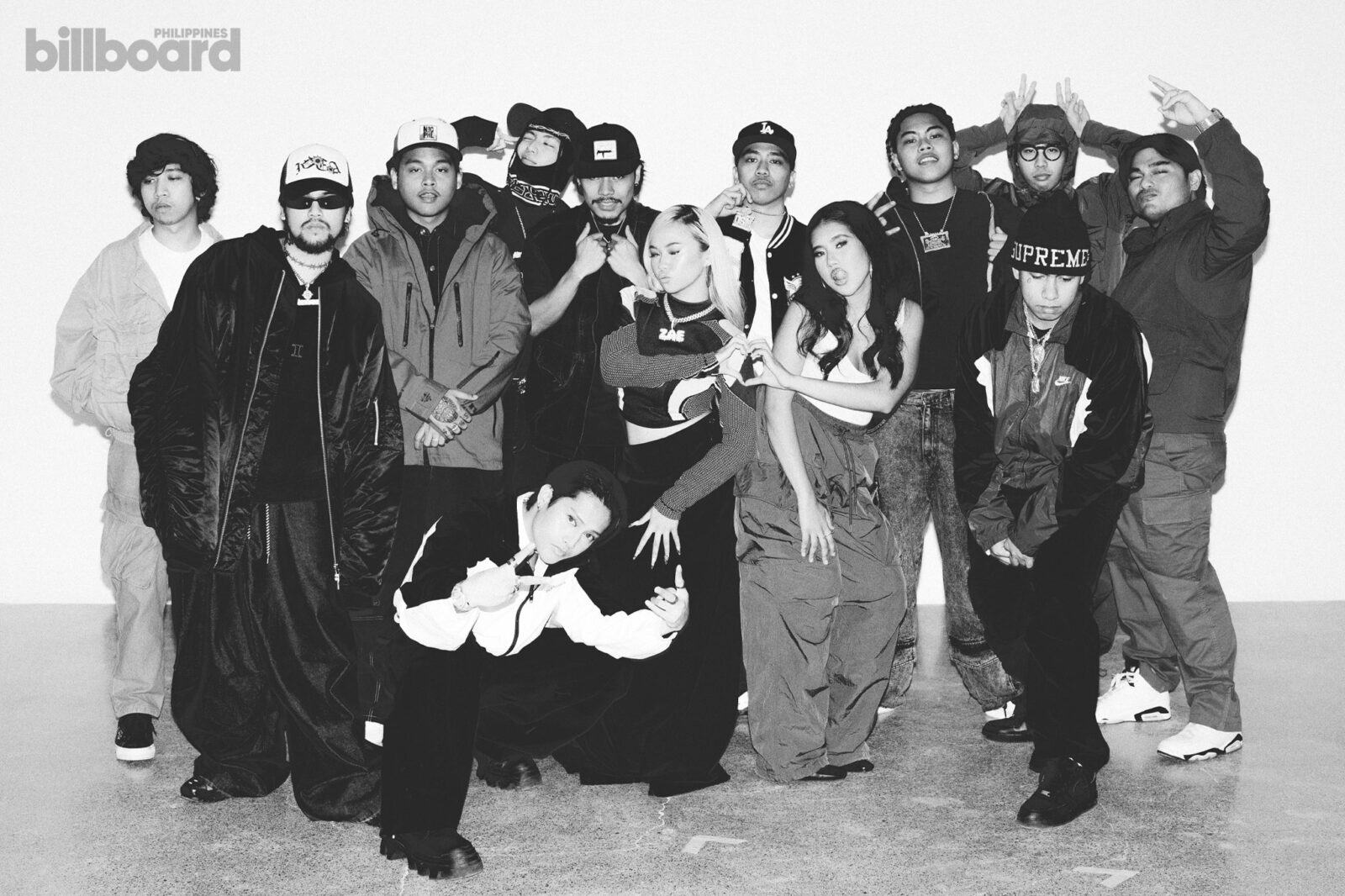

These eight acts — Costa Cashman, Madman Stan, and Gee Exclsv of O Side Mafia; Illest Morena; Hev Abi; Felip; Zae; Wave P, Luke April, and Ivo Impreso of PLAYERTWO; Al Tus and Rudyrude of Tus Brothers; and Hellmerry — are among the new generation of Filipino hip-hop acts that want to make a statement not just in the country, but in the world.

Global Force

In 2023, hip-hop music comprised nearly a quarter of all streams on Spotify globally. RapCaviar, a hip-hop playlist by Spotify, ranks as the second most-followed playlist on the app. Popular soundbites featured on TikTok videos are in part influenced by hip-hop. Certain songs are remixed to have slower or faster tempos or adjusted reverb, reminiscent of DJ Screw and the proliferation of chopped and screwed techniques. Look up the myriad of “slowed & reverb” versions on SoundCloud and YouTube, and recently, official faster and slowed versions on Spotify and Apple Music as well.

But the biggest indication of a broader cultural shift involving hip-hop is in the people. Pharrell Williams of N.E.R.D. and The Neptunes currently helms the menswear division of luxury giant Louis Vuitton. He succeeded the late Virgil Abloh, who himself was rooted in hip-hop culture, not only through his fashion background, but also as a frequent collaborator of hip-hop’s household names like Kanye West, A$AP Rocky, and Lil Uzi Vert. In hip-hop, artists are not just artists, but also creative directors, stylists, entrepreneurs — people of influence who embody a certain mode of cultural creativity that continually finds its way back into a genre.

Filipino hip-hop is having its moment as well. Last December, Spotify launched KALYE X, a series of events across the Philippines focused on hip-hop artists, in a nod to local hip-hop’s rise in streaming charts; a whopping 700% increase in the last five years.

The foothold hip-hop has in the local music scene is all the more palpable on the ground, where hip-hop artists have regularly sold-out shows in Manila nightclubs as well as regional festivals. City tours with hip-hop acts as headliners are becoming all the more common. Local hip-hop fixtures both young and old are also finding success booking shows in the United States and Canada to a receptive Filipino diaspora.

Yet even when hip-hop music dominates global charts, the genre’s leading edge always seems to be outside of the comforts of the average listener. A little too loud, or maybe a little too in-your-face. Hip-hop has always had a mean streak, and some artists have had their fair share of negative publicity. But the music itself always lends itself to a degree of experimentation, of habitually stepping over the lines.

It’s exactly hip-hop’s propensity to move faster than the speed of culture that makes it a little too advanced — and all the more exciting.

From The Streets

Despite all of this, Filipino hip-hop always appears to have a chip on its shoulder, as any of the bright young new voices of Philippine hip-hop will tell you. While the stories of how they came to be are undoubtedly different, this crop of artists appears to be both familiar and rare at the same time. Each one of them has received a certain amount of recognition, a wide amount of appreciation, and the capacity to be even bigger names than what they are now.

The sources of their influences run wide — another offshoot of social media algorithms flattening the past decades of music into a digestible format — but also run the gamut of hip-hop’s inner circles. For these rising hip-hop artists, they look up to the greats, as well as the innovators they would hear in the streets, or through lyric videos on YouTube and the semi-anonymous corners of SoundCloud.

This particular new wave of artists experienced their first contact with Filipino hip-hop through the likes of mainstream hip-hop like Gloc 9 and Andrew E, but also from those who came ahead of them and built it up to what it is today.

“‘We Don’t Die We Multiply’ ng 187 Mobstaz,” shares Zae when asked about the first local hip-hop track she remembers hearing.

“‘Kabet’ ng Gagong Rapper,” Felip answers. “[It’s a] classic, man. OG’s a legend, bro.”

Costa Cashman of O Side Mafia — a bombastic trio reminiscent of a peak Shoreline Mafia — credits an OWFUCK performance to his first time joining a mosh pit in a hip-hop gig. Meanwhile, nighttime lyrical lothario Hev Abi attributes a paradigm shift in the potential of local hip-hop to listening to Bugoy na Koykoy.

Illest Morena, known for her sharp-tongued bars, made the leap to hip-hop by way of her peer, fellow pop-rap rising star Zae. “[Noong] nakita ko siyang mag-start, doon ako nabuhayan ng loob,” she shares. “Shucks, kaya pala ng babae na gumawa ng ganitong music in the Philippines! Hindi ‘yung puro acoustic or lahat focused on one topic lang kasi doon kami kinahon.”

[When I saw her start [her career], I felt a fire light up in me…Shucks, a girl can make this kind of music in the Philippines! Not just acoustic or just focused on one topic because that’s where we’ve been boxed in.]

It’s this exact acceleration in culture, where newer acts not only pay homage but also build off of what recently came before them, that makes each new crop of artists all the more potent. This group is no exception.

But why hip-hop? While social media aggregates ideas and favors flattened, easily consumable pieces of content, hip-hop at its core has always been an avenue for the freedom of expression first rather than a medium that’s designed to be marketable or commercialized.

“Kaya pinili namin ‘yung hip-hop kasi mas madali dito mag-express ng nararamdaman (We chose hip-hop because this is where we can easily express what we feel).” shares Gee of O Side Mafia. “Kumbaga para siyang diary sa amin. Pag pakanta kasi, minsan hindi maganda ‘yung boses, kaya minsan parang alam mo ‘yun, conscious ka. Pero pag nagra-rap ka, mas madali mo siyang ma-express (That’s why it’s like a diary for us. When it comes to singing, sometimes your voice isn’t good, that’s why sometimes you get conscious [of how you sound]. But if you rap, it’s easier to express)”

For Hev Abi, there’s an undeniable cool factor attached to hip-hop, but also a creative license to experiment. “Mas nakikita sarili ko dito kaysa sa ibang genre. Dito ‘yung mga tropa. Mas makulit dito, eh (I feel most like myself [in hip-hop] than in any other genre. This is where friends are made. It’s wilder here.)”

“Minsan tumatapik-tapik ako ng iba, napupunta ako sa kumakanta-kanta, kahit rapper ako,” he continues. “Nandito ‘yung mga hinahanap ko talaga, eh. Mas dito nabibigay ‘yung ligaya ko.”

[Sometimes, I tap into other things, like sometimes I sing even if I’m a rapper. Everything I’m looking for is here. Hip-hop is where I’m the happiest.]

Ivo Impreso of PLAYERTWO also acknowledges how the horizons of hip-hop itself has widened. “Before, hip-hop was a lot of storytelling of struggle […] and now there’s more freedom to just make fun music for people to enjoy or for people to escape, to vibe,” he says. “I think it’s cool na (that) it’s become more enjoyable. There’s still music you have to think about, and there’s music where you can just have fun.”

“Itatrato na rin kami nila with respect as artists. We deserve that respect and that recognition.”

This variety in subject matter may be attributed to the fact that in the digital age, charting your own path in hip-hop has become more accessible than ever. Hellmerry, known for his collaborations with hip-hop mainstays Shanti Dope and Klumcee, charts this phenomenon up to the evolution of the genre.

“Kumbaga… evolution of music through rap kasi malawak na rin siya. Nagiging marami na ‘yung categories pero ang hip-hop parin siya. Kumbaga, mamimili ka nalang ng trip mo, eh. Kung ano, YouTube nalang, ‘type beat’ nalang, ikaw na bahala gumawa kung paano ka magiging creative (It’s like the…evolution of music through rap because it’s so broad now. There’s a lot of categories pero it’s still hip-hop. It’s like, you can pick whatever sound you like. Like, just go on YouTube, [put in] ‘type beat,’ and you have full control on how you want to be creative with it),” he says.

Rudyrude of the Tus Brothers jumps on this, saying that with the advent of SoundCloud, artists like them weren’t afraid of being experimental and fusing different subgenres of hip-hop.

“Lahat ng papakinggan mo sa SoundCloud, bago sa pandinig mo, eh. Doon nagsimula sa akin na parang, pwede pala ‘yun. Dati kasi parang may discrimination. Bawal mag-merge ang rock at rap. Ngayon kasi parang kahit ano gawin mo, respect. Bahala ka sa buhay mo,” the rapper continues. “Ayun ginawa mo. Kung ano ‘yung naisip namin, gagawa kami. ‘Di ba? Kami ni Al, lahat ginagawa namin. Techno, lahat ginagawa namin. ‘Nung super experimental kami, kung ano pwede naming mabato, go, basta just do it.”

[Everything you listen to on SoundCloud is new to your ears. That’s where it started for me, like oh, we could do that. Before, it seemed like there was discrimination. You couldn’t merge rock and rap. Now, it’s like whatever you do, respect. You do you. Whatever we think of, we do it. Right? Al and I, we’ll do whatever. Techno, we’ll do whatever. When we were super experimental, whatever we thought of, go, just do it.]

For Illest Morena, the freedom to take hold of your own sound is what makes expressing yourself through hip-hop even better. “Now everybody’s free and like, mas liberated na ‘yung artists and producers to make better music and be experimental. Pagdating sa lyrics, ‘di na nag-hold back mga artists ngayon kasi hindi na ganoon ka-conservative ‘yung mga tao at mas socially accepted [na.]”

[Now everybody’s free and like, artists and producers are more liberated to make better music and be experimental. When it comes to lyrics, artists don’t really hold back anymore because people aren’t as conservative and it’s more socially accepted.]

The Powers That Be

While there have been strides in how hip-hop has been received by the Filipino audience, the genre is still generally perceived as a low-brow art form. It’s no secret that Pinoy hip-hop has been historically looked down on by a majority of Filipinos, especially those in the higher echelons of socioeconomic class. Despite this, many have appropriated the clothes, the slang, or are die-hard fans of foreign rappers.

“Medyo nag-stem din siya from classism, kasi pang masa ‘yung hip-hop. So [there are] more people na mas prefer nila ‘yung international music (It kind of stems from classism, because hip-hop is for the masses. So there are more people that prefer international music),” shares Illest Morena. “Tingin nila sa Tagalog, basta may slang, jejemon (They think, because it’s Tagalog, because there’s slang, it’s jejemon).”

“Hindi pa rin nila maalis sa isip nila na kasi deep inside meron silang self-hate sa sarili nilang lahi at sa sarili nilang language,” she adds. “Pero nakikinig pa rin sila. Patago, kasi ayaw nilang malaman ng mga tao na ‘yun ‘yung music na pinapakinggan nila at nakaka-relate sila dito.”

[They still can’t let go of the fact that deep inside, they hate their own nationality and language. But they’ll still listen. In secret, because they don’t want people to know that they listen and relate to this music.]

For the boys of O Side Mafia, it may also be an offshoot of the conservatism that embodies Filipino culture. Pinoy hip-hop pulls no punches when it comes to tackling the taboo — money, sex, vices — and for many people, these topics go against “conservative Filipino values.”

“Kami na ‘yung meta. Kami na ‘yung god… Kami na ‘yung representative ng new wave kumbaga.”

It’s not just class struggle or values that affect this perception. Zae adds that there’s an element of colonial mentality, where our collective history of Western imperialism in the country has shaped this idea that Pinoy hip-hop is “inferior.”

“Maraming porsyento pa rin ng tao ang gustong makinig ng English kaysa mga Tagalog. Pero since na-bri-bridge na ‘yung gap ng mga nakikinig sa Tagalog rap, feeling ko kailangan natin ng mas i-support na tao ng mga tao, para ‘yung mga mas matanda, mas ma-gets rin nila kung bakit nagiging uso ‘yung mga ganyan.”

(A large percent of people want to listen to English instead of Tagalog. But now, since the gap is being bridged, I feel like we need to support each other more, so that those who are older can understand why these songs are popular.)

“Nasa utak nating mga Pilipino na just because it’s foreign music, ‘yun ‘yung standard (Filipinos think that just because it’s foreign music, that’s the stnadard),” Felip adds. “[People think], ‘I don’t want to listen to you because you’re from the Philippines.’ I want to listen to foreign music.”

Despite everything, there’s still a bright hope that the tides are changing. Hellmerry shares that even if there will be times when they wouldn’t be able to change people’s perspectives, Filipino hip-hop is still, wholeheartedly, Filipino. However, with Pinoy hip-hop getting traction in other countries, it signals that the genre can start getting the respect that it wholeheartedly deserves.

New Kids On The Block

With all their eyes set on the global stage as a benchmark of success, there is no question that Pinoy hip-hop is on its way there.

“Feeling ko kami na ‘yung mga makabagong rockstar, eh,” Hellmerry says. “Kami na ‘yung meta. Kami na ‘yung god… Kami na ‘yung representative ng new wave kumbaga.”

[I feel like we’re the new rockstars. We’re the meta. We’re the god…we’re the representative of the new wave.]

And with the new wave comes infinite possibilities. All eight acts dream up what the country’s hip-hop scene could look like — all of them hope for a future where Filipino hip-hop artists will get the respect and just compensation that they deserve. They hope that they’ll no longer be branded as ‘jejemon’ or shortchanged.

“Itatrato na rin kami nila (They’ll treat us) with respect as artists. ‘Yung iba sa amin, kami na rin ‘yung gumagawa ng sarili naming music, nagpro-produce (Some of us make our own music and produce it). We deserve that respect and that recognition,” Illest Morena shares as she calls for people to stop branding hip-hop as an inferior genre.

There’s no reason why the whole country shouldn’t rally behind the hip-hop community. From the streets to the screen, hip-hop is no longer seen as a niche interest, but a driving force that speaks to the culture of today. These eight acts do not only represent what the kids are listening to today but also speak towards an exciting future — one that aims to represent the Philippines on the international stage. The timing’s just right, and there’s Filipino talent ready to go big under the hip-hop blueprint on the global stage.

The question is: is the rest of the world ready?

As Al Tus puts it succinctly: “[It’s] inevitable. Hindi mo mapipigilan. Maririnig talaga tayo ng buong mundo.” [You can’t stop it. Everyone in the world is going to hear us.]

Photographed by Everywhere We Shoot. Assisted by JV Rabano and Don Calopez. Creative and Fashion Direction by Daryl Chang. Assisted by Kurt Abonal. Art Direction by Nicole Almero. Hair (Costa Cashman, Gee Exclusv, Madman Stan, Hev Abi, Al Tus, Zae, Rudyrude, Ivo Impresso, Luke April, Wave P, Hellmerry) by Nix Institute of Beauty & Makeup (Costa Cashman, Gee Exclusv, Madman Stan, Hev Abi, Al Tus, Zae, Rudyrude, Ivo Impresso, Luke April, Wave P, Hellmerry) by Estee Lauder PH. Hair (Felip) by Mark Familara. Makeup (Felip) by Mac Igarta. Shoot Coordination by Mikaela Cruz.