Stray Kids Have Become Global Stars By Giving ‘Strength To People Who Really Need It’

With a No. 1 project, two mega-labels behind them and eight undeniable personalities, Stray Kids are positioned for superstardom — and sound ready for the challenge.

From left: I.N, Hyunjin, Felix, Changbin, Lee Know, Bang Chan, Han, and Seungmin of Stray Kids photographed by Ssam Kim on July 13, 2022 at The Ruins in Seattle. Styling by Park Jung Ah and Park Yeri. Hair by Hee U and Kim Minju. Makeup by Jun Jiwon and Park Jinhyeong.

Stray Kids’ Felix gazes out into an arena crowd — a strand of jet-black hair bouncing on his forehead — and turns his palms upward. “The new generation is here.”

For hours, the K-pop eight-piece had incited shrieks during a breathless performance at the Prudential Center on June 29, the second night of two back-to-back sold-out shows at the Newark, N.J., arena. Yet the response to Felix’s declaration is particularly deafening. Some teens and tweens in the crowd feverishly brandish their orb-like glow sticks as their parents respectfully applaud. “We are the new generation — we’re born into this world like fresh rain,” Felix continues in a measured tone while explaining the motivational hip-hop track “Muddy Water.” Group leader Bang Chan, gripping a bottle of water to recover from breakneck choreography, picks up the thread with a playful smirk: “So it’s like, we’re the new, fresh water to wash out the muddy water.”

From left: Bang Chan, Hyunjin, Han, Lee Know, Felix, Changbin, Seungmin and I.N of Stray Kids photographed on July 13, 2022 at The Ruins in Seattle.

Ssam Kim

Are Stray Kids — with their high-flying dance moves, bullet-time rapping, chest-thumping lyrics and visuals that suggest eight superpowers forming an unbreakable bond — positioning themselves as the heroes of a new K-pop wave? “That’s a bit too big for us,” says Bang Chan, leaning forward in his chair during a group sit-down in Seattle two weeks after the Newark show. “What I can say is, we’re definitely trying to put on a good impression and be as genuine as we can for people who look up to us.” That includes their millions of young fans, who call themselves STAY and who have found a home in the group’s amplification of separate talents and personal quirks. Stray Kids admit to feeling the burden of expectation but welcome it wholeheartedly. “Our goal ever since we debuted was to reach as many ‘stray kids’ as possible,” Bang Chan continues, “to deliver our music and give strength to people who really need it.”

Korean pop music finds itself in a state of transition after a whirlwind, record-breaking half-decade. Stateside interest continues to soar — consumption of world music, which includes K-pop, grew by 26.4% in the first half of 2022 compared with the same period last year, according to Luminate’s midyear U.S. charts report. But BTS, the group responsible for nearly one-third of all K-pop sales and streams in the United States over the past 18 months, recently pressed pause on group activities — the outfit had gone nonstop for a few years, and required military service loomed for some members — creating something of a void (at least temporarily) at the top of the genre.

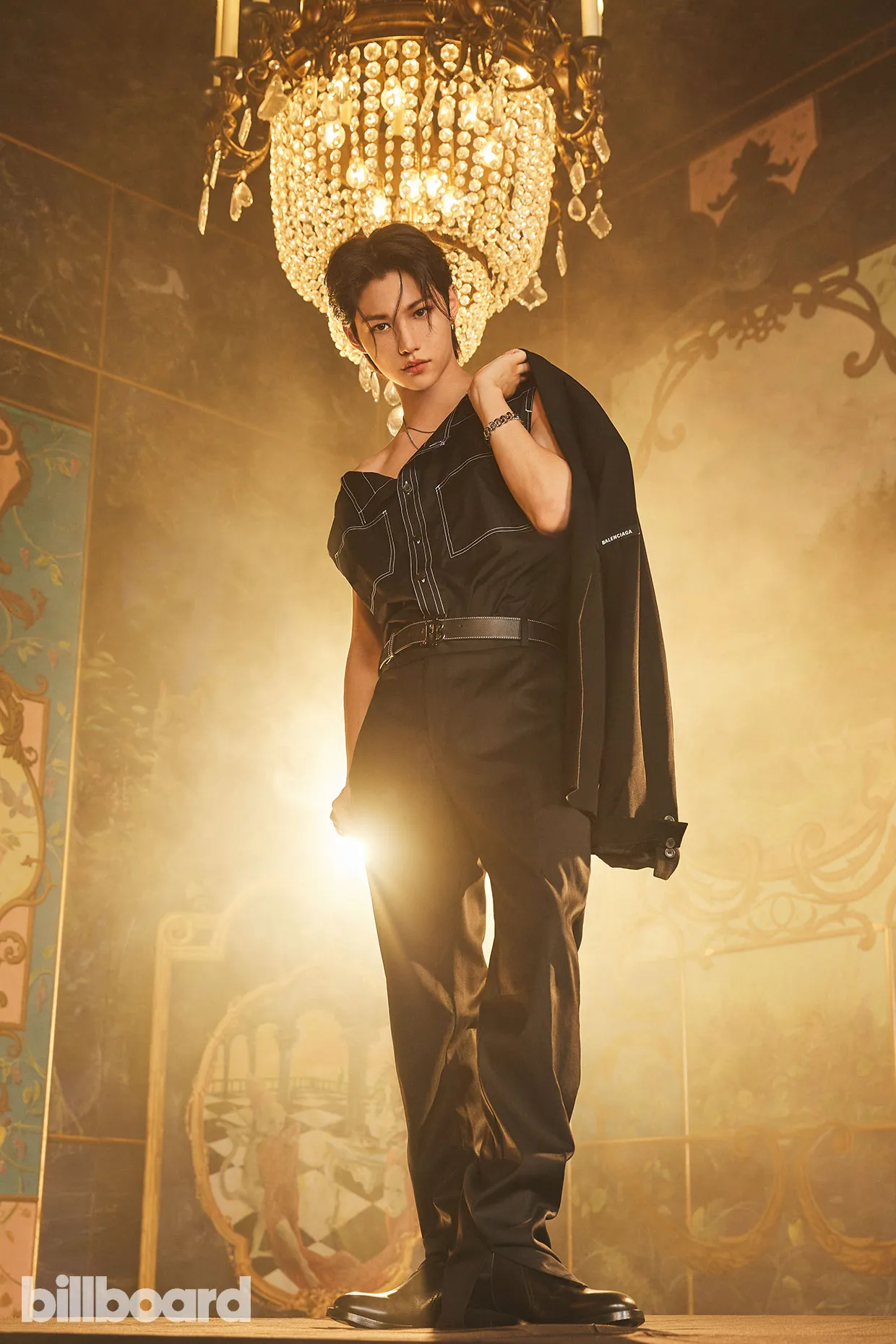

Changbin

Ssam Kim

In a market that often downplays individual personalities in favor of cohesive units, Stray Kids have become the right boy band at the right time by proudly letting their freak flags fly and inspiring others to do the same. Oddinary, their EP from last March that’s all about normalizing idiosyncrasies — and gives each of the Kids ample room to shine — became their breakthrough project in North America, debuting atop the Billboard 200 with 110,000 equivalent album units in its first week, according to Luminate, and helping Stray Kids reach No. 1 on the Artist 100 chart.

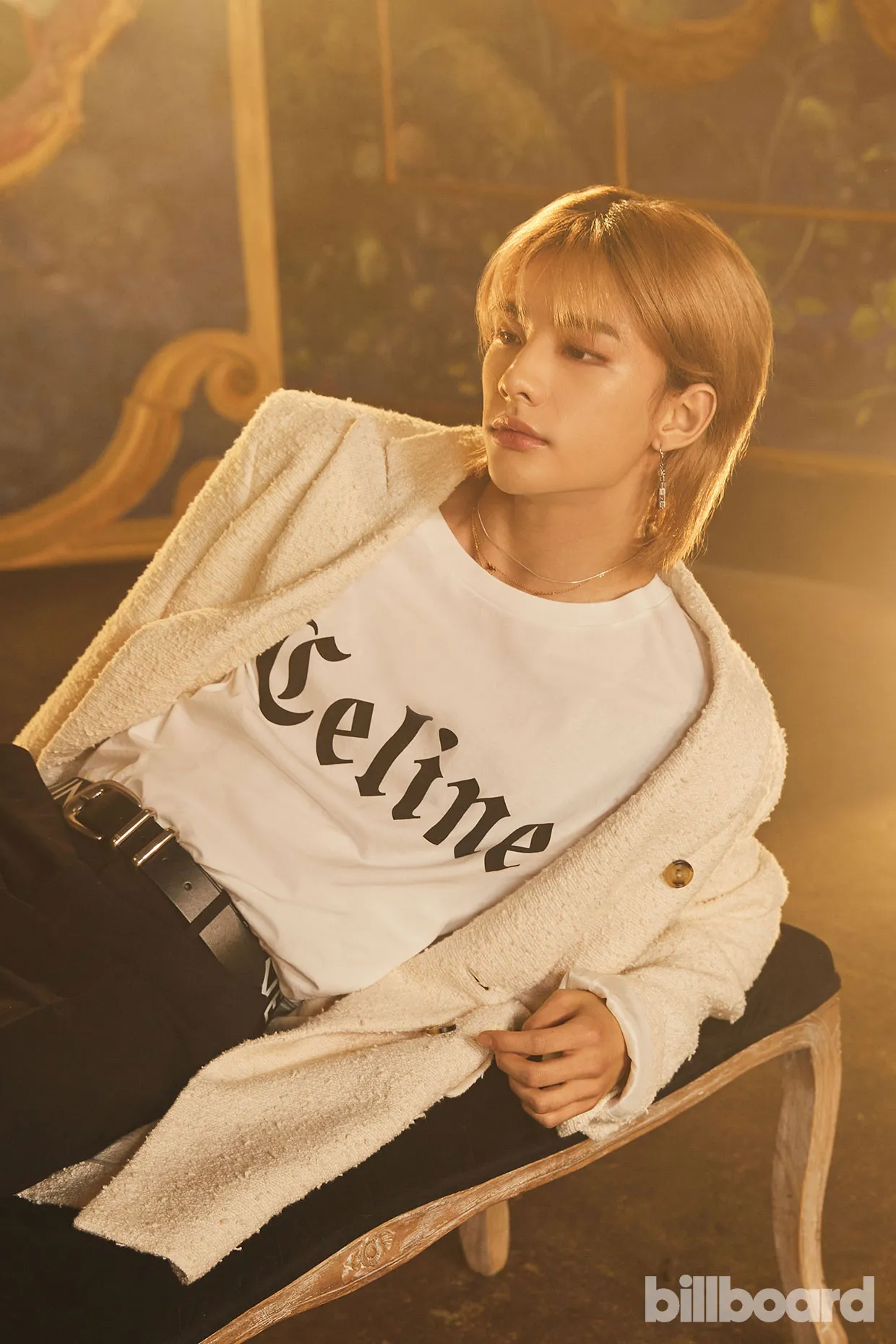

Felix

Ssam Kim

Meanwhile, the group’s Maniac world tour highlights the respective personalities of the eight members, who range between 21 and 24 years old, in different ways. In Newark, for instance, Seungmin earned cheers by covering Justin Bieber’s “Hold On.” Changbin dazzled by landing a one-handed cartwheel. And Bang Chan earned cred by rocking a Nirvana T-shirt. The tour has played to sold-out arenas in markets large and small, with the younger crowd staying on its feet for the entire, Springsteen-esque three-hour run time. Through five shows reported to Billboard Boxscore to date, the trek has sold 62,000 tickets, and its recent 10-show North American tour is expected to gross north of $16 million.

“This is a highly engaged fandom, and they’re selling out arenas and large venues in minutes,” says Glenn Mendlinger, executive vp of Republic Records and president of Imperial Music.

Han

Ssam Kim

Stray Kids are now being pushed toward global stardom by a pair of major labels on different continents, thanks in part to a strategic partnership between Republic, JYP Entertainment and Republic imprint Imperial Distribution. Republic’s deal with JYP — a Seoul-based juggernaut whose groups GOT7 and TWICE helped the company compete with HYBE (whose main group is BTS), YG Entertainment and SM Entertainment over the past 15 years — expanded earlier this year to include Stray Kids and ITZY, after beginning in 2020 with TWICE.

Stray Kids’ Han compares having JYP and Republic in their corner to working with “two Nick Furies” who guide their respective team of K-pop Avengers. Whichever Marvel reference fits to get there, Mendlinger foresees the partnership as having a common goal for Stray Kids: “global domination.”

Hyunjin

Ssam Kim

It took five years and several projects for this opportunity to arrive. Joining as teenagers in 2017 through a JYP-organized reality show of the same name, Stray Kids launched as a nine-piece before solidifying its current lineup of Bang Chan, Lee Know, Changbin, Hyunjin, Han, Felix, Seungmin and I.N by the end of 2019. Stray Kids spent years releasing EPs and rehearsing for their broader commercial debut under the tutelage of J.Y. Park, the veteran artist turned executive and superproducer who founded JYP in 1997. Park is a titan in the K-pop industry known for his exacting approach toward his groups, yet the Kids say that the label leader gave them the freedom to use their voices in the creative process, especially as they found their sea legs as a collective.

“We made music even before our debut, but in the beginning, there was a lot of feedback compared with now,” says Changbin. “We were immature in some aspects. Now [Park] trusts us wholeheartedly, the stories we want to tell with our music.” Hyunjin — who took a brief hiatus from the group in 2021, after sharing his “deepest apologies” for rumors about inconsiderate behavior in his youth — adds that “his comments were really helpful about stage manner, our future. He cares a lot about each individual’s mental health.”

I.N.

Ssam Kim

The extended development period also helped Stray Kids evolve artistically: All of its members contribute to the writing process, while Bang Chan, Changbin and Han make up the in-house production team 3RACHA and help dictate the group’s musical direction. As Stray Kids began to tour internationally — they first performed in U.S. theaters in early 2020 — that hands-on creative approach underlined an authenticity that they could present onstage. “They create their own music and add their own personal messages into their music,” says Shannen Song, executive vp/GM of Division 1 for JYP, who has worked with Stray Kids since 2017 and has watched them grow into their early 20s. “People can distinguish who has sincerity in their music … That’s the biggest strength for their music and for them.”

While Stray Kids’ international profile has expanded over the past year, they’ve naturally been compared to fellow K-pop groups, most regularly BTS. Yet one listen to Oddinary would demonstrate to casual fans that Stray Kids sound nothing like BTS, which broke boundaries for Korean artists in North America by crossing over with disco-inflected pop smashes like “Dynamite” and “Butter” before announcing a temporary group break in June. Stray Kids, on the other hand, approach pop by way of rap, rock and electronica, exploring trap, G-funk, punk and even a little industrial. Those expecting standard boy-band fare would be surprised to hear “Lonely St.” sounding Warped Tour-ready or that “Muddy Water” is closer to Odd Future than *NSYNC.

“From a genre perspective, they’re a little bit more edgy and angular than some other K-pop bands, which may be a little more sugary,” says Mendlinger. “We felt there was a huge opportunity in the American marketplace because of that little slanted angle.”

Bang Chan

Ssam Kim

Stray Kids were in Seoul on March 28 when they found out early that morning that Oddinary debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard 200, still shaking off sleep and needing a few moments for the accomplishment to sink in. “We were overwhelmed and a little bit shocked,” Felix recalls. For Mendlinger and his team at Imperial, however, they had been targeting a No. 1 debut for the project in the six months leading up to its release.

The team’s priority was to amplify Stray Kids’ presence at U.S. big-box retailers, which had been practically nonexistent prior to the JYP-Republic partnership. Collectible packages have become crucial in modern K-pop — with physical sales having as much, or more, influence on an album’s chart performance as its audio streams — and Oddinary arrived with seven total CD configurations that contained keepsakes like posters and photo cards, including exclusive editions at Target and Barnes & Noble. An indie retail blitz, direct-to-consumer initiatives and Stray Kids autographing physical editions for the first time in their careers helped Oddinary bow with 103,000 in album sales in its debut week — the biggest sales debut of the year at the time.

The No. 1 debut was part of a “renaissance” taking place for K-pop at North American retailers, says Mendlinger, with different configurations of collectibles being manufactured in Korea, shipped overseas to meet growing demand and ultimately appearing on store shelves for release week. Mendlinger notes that U.S. manufacturing of physical products, including vinyl, is expected to increase in the future. For now, Imperial’s focus is on distributing the tons of goodies being sent their way from overseas. “We are importing so much physical product,” he says, “that we are actually renting and booking 747 cargo planes and filling them with products to come to America.”

Seungmin

Ssam Kim

That international coordination underlines the importance of the JYP-Republic alliance when it comes to breaking acts like Stray Kids across different territories concurrently to their growth in Korea. Instead of waiting for acts to become superstars in South Korea before marketing them overseas, the K-pop industry is increasingly showcasing groups like Stray Kids to audiences around the world — and sometimes even more than to Korea-based fans due to collapsed language barriers and wider touring opportunities. Although Stray Kids have yet to score a top 20 hit in Korea, their popularity is being fueled by their bilingual songs, tour dates outside of Asia and Republic, 2021’s top-charting U.S. label that is working to break them even bigger.

“Republic is trying their best to understand K-pop, and we want to learn the United States market from Republic,” says JYP’s Song. Instead of preparing every detail of a release in Korea and relying on U.S. distribution, the JYP and Republic teams say that they’re in constant communication about details of their shared campaigns, from A&R to release strategies to touring markets. Mendlinger says that there are weekly Zoom calls between teams and constant WhatsApp exchanges. Ideas about package designs and TikTok trends will ping-pong among time zones. “The most important reason [for our success],” Song continues, “is that we are respecting each other and each other’s expertise.”

Lee Know

Ssam Kim

The JYP-Republic partnership formed when the coronavirus pandemic forced Stray Kids off the road for over two years. Han says that the group rested and spent time with their respective families during the break, while also “making our skills stronger” by learning new choreography in self-isolation, working on their vocal ranges and challenging themselves as writers and producers. They spent a few weeks training for the Maniac tour so that they could physically withstand a three-hour set that includes plenty of group choreography and concurrent dancing. And they kept creating new music when the tour kicked off in April. None of the members can agree on how many songs they’ve collectively worked on while touring, but the final number may approach 50.

While Oddinary delivered Stray Kids to physical retailers in North America, Republic/Imperial will focus on additional sectors for Maxident, their U.S. follow-up mini-album due out Oct. 7, including more digital activations and, ideally, more tour dates and in-person release events. And although Stray Kids have yet to chart a song on the Hot 100, Mendlinger expects to be “dipping our foot into the radio world more” in order to continue their mainstream expansion. Zooming out, Song says that Stray Kids’ schedule is roughly planned for the next few years and that research is already being completed to see which untapped touring markets — in Europe, Asia and elsewhere — make sense for the near future.

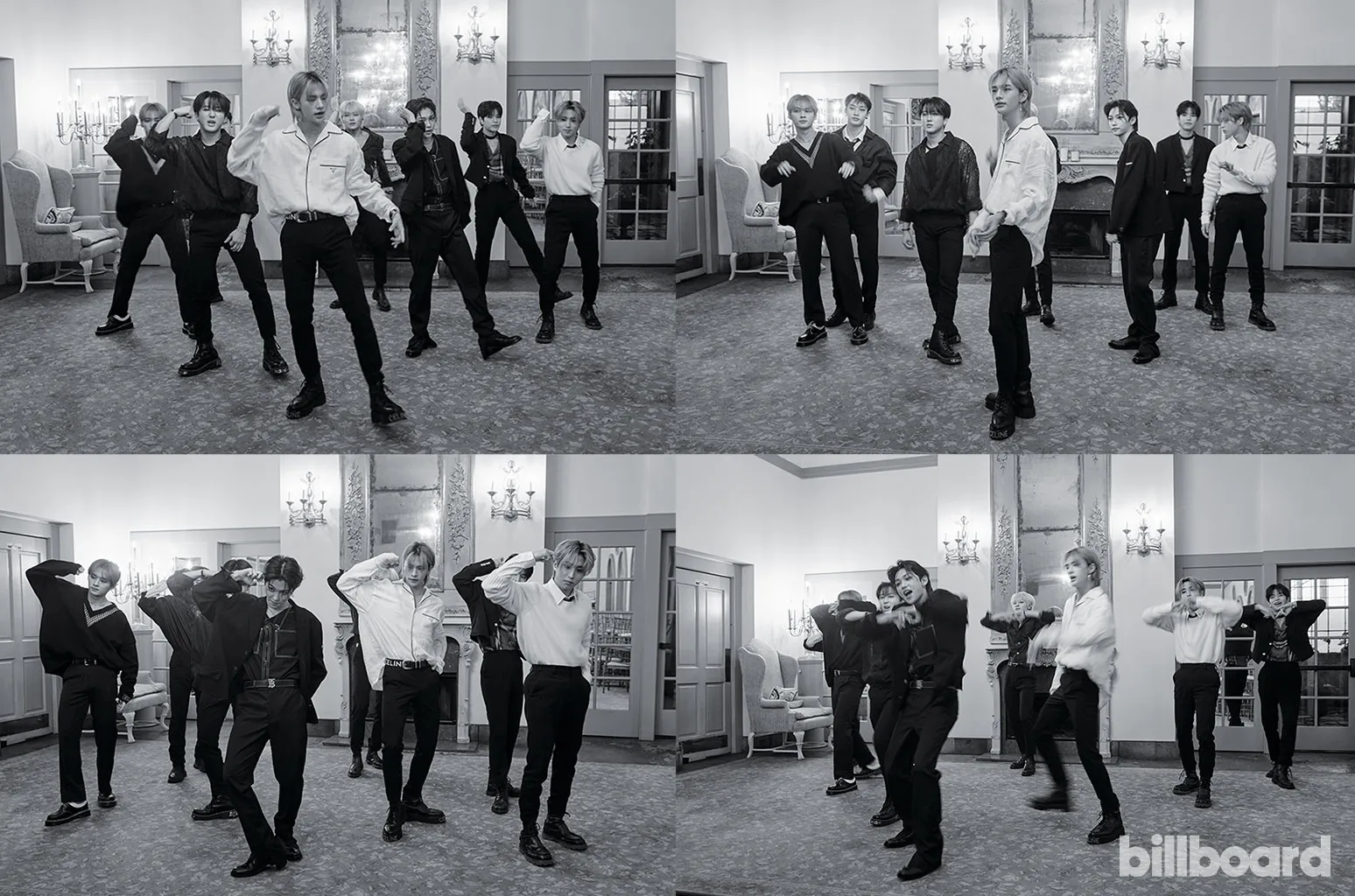

Stray Kids photographed July 13, 2022 at The Ruins in Seattle.

Ssam Kim

Six months ago, Stray Kids were viewed as a promising K-pop group with a left-of-center sound. As the arena shows and anticipation for new music quickly build, they’ve adjusted on the fly to being seen as potential superstars. “Pressure is something that we all feel,” says Bang Chan, widening his arms to encompass the entire group. “But I feel like that pressure just energizes us more.” Although Stray Kids joke around with one another like a college-age clique with an endless list of inside jokes, they also take their job as new-school role models seriously. The word “responsibility” pops up often in conversation, and when they reflect upon the thousands of adoring screams they hear each night on the road, Stray Kids have all the motivation they need to keep traveling the globe.

Ultimately, the group rejects complacency, and that outlook helps keep it focused as it barrels toward superstardom. Stray Kids are grateful for everything they’ve achieved to date but refuse to be satisfied: They want to get bigger and better, and mean the most to as many people as they can. “If we settle, we know we can’t go forward,” says Han. “That’s why we were and are like this. We try to look ahead and not stay still.”